- Sales: 0800 368 9086

- Service: 0800 970 8207

Sustaining the well-being and longevity of tens of millions of Brits, hospitals and medical centres make up the foundation of our country’s healthcare system. The typical week witnesses over 300,000 hospital admissions, with most of those inpatients being admitted through Accident & Emergency (A&E). Then there’s the A&E patients who are treated and discharged, outpatients who visit for routine referrals, and those that are admitted for scheduled life-saving surgeries – all of which inflate the figures further.

With such a busy and important role in our society, it’s crucial that hospitals remain sterile for patients, staff, and visitors alike. Patients deserve to receive treatment in a safe and hygienic environment – a setting that will prevent the spread of illness and provide a calming, comforting presence for their recovery. The same goes for members of staff – clean facilities will help boost morale, decrease absences, and raise the overall standard of care they’re able to provide.

For these reasons, the NHS have delegated ample resources into developing a cleaning framework that will aid local trusts and practices in maintaining hygiene standards. This document is continually updated, with the most recent version (that of 2021) available here. Countless requirements and recommendations are made by the framework, with many such points proving critical to the CQC infection control audits that hospitals will later come to face.

In Vanguard’s latest blog, we’ll run through the hygiene standards outlined in this document. From colour-coded equipment and cleaning schedules to risk assessments and rigorous auditing, we’ll discuss the vital cleaning standards that are so frequently employed by hospitals and medical facilities across the nation.

With so much at stake, it’s crucial that hospitals and practices follow the main principles of cleaning, and understand how the various techniques and methods at their disposal could help or hinder their efforts. Therefore, we’ll take a look some of the most important and commonly-used definitions to gain an understanding of the basic science behind healthcare cleaning:

Cleaning – Often used as a catch-all term, the scientific definition of cleaning is a tad trickier. Cleaning a surface involves the use of a ‘fluid’ (typically water with detergent), and ‘friction’ to rub off any dirt, grime, or harmful pathogens, which leaves the surface looking visibly clean. Important to note is that cleaning does not kill bacteria – instead, just like soap, it displaces and dislodges the organic matter rather than destroying it.

In this way, cleaning is more useful for lower risk areas, such as a reception area, but usually not robust enough for more vulnerable rooms, such as an operating theatre. For these more susceptible areas, cleaning will often serve as a prerequisite for further measures, like disinfection or sanitisation.

Disinfection – Unlike simple cleaning, Disinfection involves the elimination of MOST harmful pathogens on a surface, using a disinfecting agent.

Sterilisation – Going a step further, Sterilisation involves the elimination of ALL harmful pathogens on a surface, usually by strong chemical agents or high temperatures.

Decontamination – Refers to the process of decontaminating an area, which may include Cleaning, Disinfecting, Sterilising, or any combination of these methods. Most commonly, the term refers to the two-step process of cleaning & then disinfecting a surface.

In most cases, the specific techniques and products to be used will depend on the policies and procedures of the local NHS trust. While there may be some minute differences between how different hospitals handle their cleaning, the overall hygiene standards (and the scientific reasoning behind it) will broadly remain similar to one another.

Turning elsewhere, important principles are also in place when it comes to cleaning frequency, defining how often and how thoroughly different objects and areas must be tended to. The primary definitions are listed below:

Full Clean – Involves cleaning all elements of the object, using the appropriate techniques until visibly clean.

Spot Clean – Involves cleaning specific elements of the object, using the appropriate techniques until visibly clean.

Check Clean – Involves checking the object to assess if specific elements align to performance parameters. If not, a full clean or spot clean must be completed.

Periodic Clean – Involves a full clean of an object at periodic intervals, such as monthly or quarterly. Anything less frequently cleaned than monthly is considered not routine, and should form part of a planned annual programme.

Touch Point Clean – Involves a full clean of objects that are regularly touched, using the appropriate techniques.

You’ll see these definitions across many hospital cleaning schedules, providing key information to assigned staff on how certain cleaning tasks should be handled.

The NHS framework outlines a series of best practice guidelines that are relevant for every type of facility and every kind of risk level. This guidance helps form the basic cleaning protocols that become part and parcel of hospital cleaning standards, which includes the following key points:

Of course, with so much specialist equipment involved and such a complexity of wards, consulting rooms, receptions, and operating theatres to contend with, creating a hospital cleaning schedule becomes a complicated affair. As such, NHS guidance makes it clear that cleaning schedules must be outlined in great detail, going so far as to list every object and surface of a room, and assign each cleaning task to the person(s) responsible as well as clarify how often each task must be performed.

The creation of such a schedule is therefore no simple matter, and requires a significant investment of time and effort by hospital management. Once completed, however, a cleaning schedule serves as a comprehensive checklist, ensuring everyone involved understands what is required of them at what time. This helps avoid anything slipping through the cracks, which has previously been known as an all-too-common pitfall in hospital cleaning.

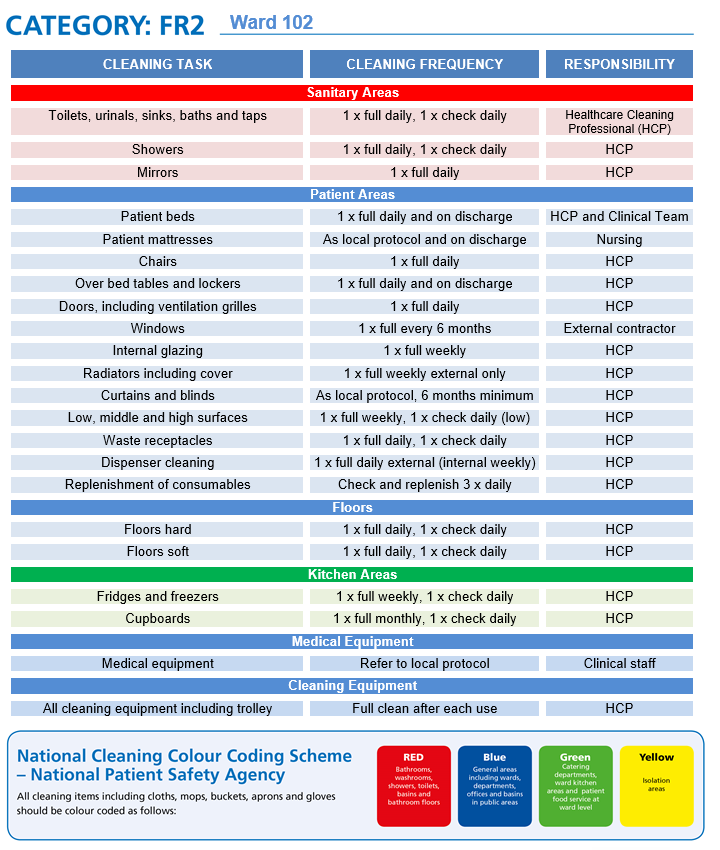

As an example, see the below image for what a cleaning schedule might look like for a hospital ward:

*All images in this article have been taken from publicly available NHS documentation available here*

This cleaning schedule lists all the objects and items found in a typical ward. You’ll probably notice that the schedule is divided and colour-coded by object type and risk level. You may also notice in the top-left corner that the ward has been categorised as FR2. We’ll delve into both of these aspects later, but for now, let’s focus on the rows and columns themselves.

The schedule consists of three columns – Cleaning Task, Cleaning Frequency, and Responsibility. The following rows then detail which tasks need to be completed on what time frame by which individuals, with Healthcare Cleaning Professionals (HCPs) responsible for the vast majority of duties. Consisting either of in-house staff or external contractors, HCPs possess the broad training and expertise to clean, disinfect, and sanitise anything found in a medical environment. There are even national bodies of like-minded professionals, including the Association of Healthcare Cleaning Professionals (AHCP), an organisation that Vanguard is proud to be endorsed by.

Naturally, the finer details of cleaning schedules will often be determined by the specific conditions and requirements of the local trust. With each hospital being unique, a blanket approach simply won’t work, and it will instead be down to each site’s management to make changes as needed to the frequency or responsibility of cleaning tasks. For this reason, each hospital’s cleaning schedules should be uniquely tweaked to their specific needs, whilst incorporating much of the existing cleaning framework as standard.

Now let’s turn to the colour-coding that can be seen on the schedule. Sanitary areas are coded in red, kitchen areas in green, and other areas in blue. This corresponds to the National Colour-Coding Scheme, which has been implemented in healthcare facilities across the country to ensure uniformity and reduce cross-contamination.

Only the corresponding-coloured equipment (including mops, buckets, and brushes) should be used in each zone, and never used in a different colour zone. The colour codes are as follows:

Red – Sanitary Areas. Examples include bathrooms, toilets, sinks, basins, showers, baths, and bathroom floors.

Blue – General Areas. Examples include wards, departments, corridors, waiting rooms, offices, consultation rooms, and receptions.

Green – Food Areas. Examples include catering departments, canteens, kitchens, and patient food services.

Yellow – Isolation Areas. Examples include clinical equipment and infectious zones.

Colour coding was first introduced by the British Institute of Cleaning Science (BICSc) in the late 1990s, and has since been widely adopted by organisations up and down the country. Today, the code is standard practice in most hospitals and healthcare environments.

You may have noticed that in the cleaning schedule, the hospital ward is categorised as FR2, which stands for Functional Risk level 2. This is one of the higher risk categories, likely due to the close proximity of patients to one another, meaning illness could spread around the ward rather quickly. For operating theatres and vulnerable areas, the standards of cleaning required will be more stringent, while waiting rooms and offices won’t need such rigorous attention.

For this reason, the NHS outline that all rooms and areas in a hospital need to be assessed for their hygiene risk level, and assigned a code from FR1-FR6, with FR1 being the most susceptible to harmful pathogens and FR6 the least. Each risk level will require a different standard of hygiene – FR6 might only need regular spot cleaning, while FR1 could require full sterilisation. Generally, it’s considered good practice for facilities to use all 6 categories, allocating different risk levels to areas as needed, although it’s worth noting that this is not mandatory.

Many trusts choose to use a blended approach, such as 25% FR1 and 75% FR2, or something similar, which would classify as FR2 blended overall. As we’ll see next, these risk levels prove instrumental to the frequency and scrutiny that hospitals are monitored and audited with.

Monitoring & auditing procedures are particularly important for hospitals, as any lapse in hygiene could have catastrophic consequences for vulnerable patients. Robust auditing is therefore crucial to maintaining hospital hygiene standards, ensuring any errors or oversights are escalated and duly addressed.

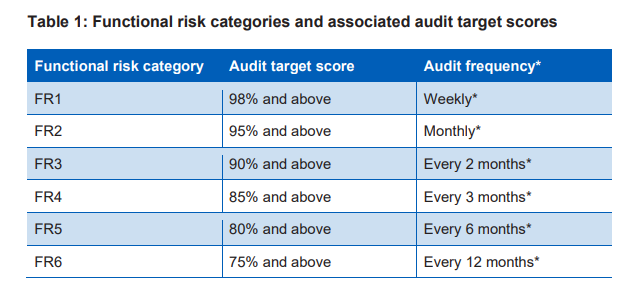

Hospitals handle auditing through the aforementioned risk categories, like FR1 and FR2. Each risk category is given an Audit Target Score that outlines a certain percentage of the area that must be up to standard, and an Audit Frequency, which specifies how often an audit must be carried out. The aim is to provide an in-depth and reflective assessment of hygiene across a broad area, with a minimum of 50% of the zone being assessed at any one time.

The functional risk categories and corresponding scores are listed in the table below:

*All images in this article have been taken from publicly available NHS documentation available here*

For example, an area categorised as FR2 will undergo an audit every month, and is required to earn a score of at least 95% to pass that audit.

While these percentage scores are used primarily for internal monitoring, many hospitals also use a five-star cleanliness rating system for external verification. The percentage score they earn will correspond to a cleanliness rating, like 4 or 5 stars, which makes for an easier way to display auditing results to the public. This is because many common rating systems, like restaurant hygiene and hospitality reviews, also use a five-star rating system, making it clear and instantly recognizable to the general populace.

In the case where a blended FR approach is used, an average target score is calculated based on the number of rooms and their FR category, meaning unique target scores such as 87% or 93% might be in place depending on the circumstances surrounding the premises.

With so much to take into account with healthcare cleaning, it’s all too easy to fall into one of the many pitfalls that could prove disastrous to your practice and patients. As such, the help of a professional medical cleaning company might be needed.

Founded in 2002 as a specialist medical cleaning company, Vanguard Cleaning has grown significantly over the past years, acquiring a breadth of experience across medical centres, doctor’s surgeries, dentist’s offices, clinics, and specialist practices. In this time, we’ve developed a comprehensive cleaning framework in line with the NHS, detailing everything from risk management to monitoring protocols. Of course, this is all designed with the CQC and HIW in mind, helping ensure compliance and making audit difficulties a problem of the past.

With accreditations from both the Association of Healthcare Cleaning Professionals (AHCP) and the British Institute of Cleaning Science (BICSc), Vanguard stand foremost among the professionals and experts in the industry. This expertise extends down to our cleaning staff, who are instructed rigorously by our Area Managers to equip them with the full knowledge needed to clean a diverse range of medical and clinical areas.

In every case, we’ll tailor our cleaning solutions to your practice, crafting unique cleaning schedules and risk assessments that target your specific needs at their source. For more information, and to learn how Vanguard can keep your healthcare site spotless and sterile, be sure to contact our professional team today.